Nel decennio a cavallo tra i settanta e gli ottanta, la tecnologia rese possibile ai musicisti organizzare studi casalinghi, creare musica, e distribuirla in maniera indipendente dalle grandi etichette discografiche e dalle produzioni commerciali. Durante questo periodo si crearono tra i musicisti indipendenti organismi per la comunicazione di informazioni e per lo scambio musicale. Uno di loro, l’International Electronic Music Association (IEMA), pubblicò cassette compilative, rappresentative dei suoi membri musicali. La prima di questa serie di nastri è stata resa disponibile in digitale, unitamente ad altri progetti che mirano a preservare e diffondere il lavoro di questo sottobosco antico della cassetta.

One of the more interesting trends of recent years is the resurgent visibility of the cassette tape as a medium for creating and distributing music. Experimental and electronic musicians have long had a durable relationship to tape as a medium for creating as well as for storing sound, but since the middle of the last decade cassette tapes have been appearing with increasing frequency among new releases of experimental as well as other kinds of music. At the same time, the ascendency of digital technologies has made possible the preservation and perpetuation of the work of one of the more significant forerunners of contemporary experimental music: The original cassette underground.

An inexpensive means of recording and reproducing sound, beginning in the 1970s cassette technology made it possible for musicians to set up home studios, create music, and distribute it independently of major labels and commercial outlets. Like the mail art movement which it paralleled and which to some extent provided a model for it, the cassette underground embodied a DIY aesthetic facilitated by access to low-cost, ready-to-hand materials.

If the appeal of cassettes then was largely economic, their appeal today consists in part in their tangibility. The physical objecthood of the tape serves as a kind of counterbalance to the seeming immateriality of the digital download. But there may in addition be something attractive about the coloration cassette tapes unavoidably give to the music they contain. The inherent peculiarities of sound reproduction on tape—its relative low fidelity, the signature hiss, its potential for mechanical unreliability and its being subject, as a magnetic medium, to a natural deterioration over time—add something of an element of aleatory play into the sound of the recorded music: An inadvertent, chance-based, very post-production layer of sound manipulation moving toward its own self-effacement.

In a sense the renewed interest in cassettes represents a reaffirmation of roots. Many experimental and electronic musicians working today spent their formative years as part of the cassette underground that was particularly active in the 1970s-1990s. Artists such as Al Margolis, who issues provocative electroacoustic work under the If, Bwana name; Hal McGee, whose HalTapes continues to foster low-fi experimentation; and Don Campau, like McGee an historian of cassette culture as well as a creator of home-recorded music, all were involved in the cassette underground and, as artists and/or archivists, have kept its legacy relevant as a creative force in the 21stcentury.

Despite the inherent ephemerality of the medium, works from the cassette underground’s flourishing during the 1970s and 1980s are finding their way to archival reissue programs. Paradoxically, these works are being archived and disseminated through the digital means that provoked the recent cassette revival in the first place. But the paradox is one based on continuity rather than contradiction; these digital reissues of historic tapes are simply another, late link in a chain of traditions tracing back to a point of analogue origins, preserving the memory of homemade electronic music networks in the process.

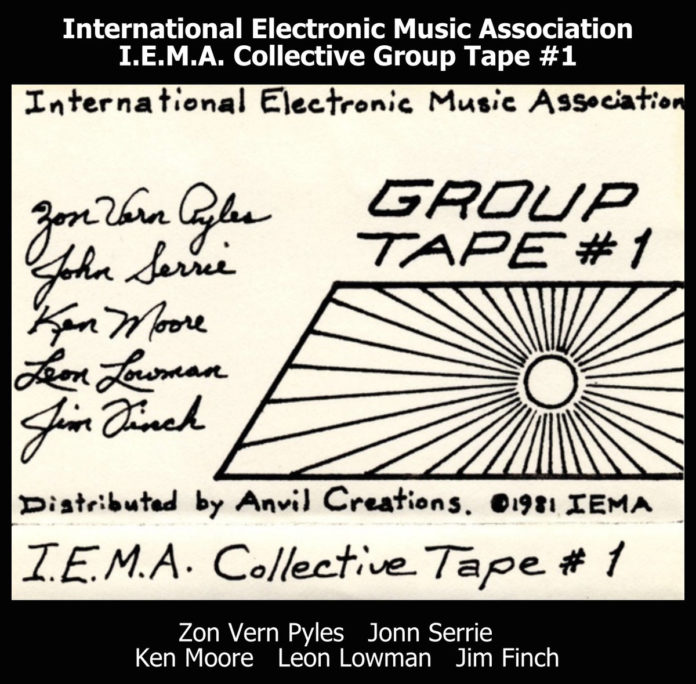

Before the Internet came into widespread use, a nexus of formal and informal groupings of experimenters and enthusiasts, both amateur and professional, was what made the cassette underground’s gift economy of tape exchanges thrive. One such group was the International Electronic Music Association (IEMA), which was formed by Jim Finch in New York State, USA in 1978. Established at a time when analogue synthesizers and Mellotrons were becoming widely available, IEMA was a means for putting geographically-dispersed synthesizer users in contact with each other, first with a four page mimeographed newsletter and later with the zine SYNE. IEMA, which was active through the mid-1980s, was a truly international and democratic association: In addition to amateur enthusiasts and aspiring musicians its membership included such better-known names as Klaus Schulze, Larry Fast, Maurizio Bianchi, Bernard Xolotl, Don Slepian and even Yanni.

Besides disseminating information, IEMA issued a series of cassette tapes collecting examples of members’ work. Initiated by Finch, these samplers were put together by Ken Moore, an early member who served as the group’s music director for three years beginning in late 1979. Moore—pictured above in 1978–began as a progressive rock musician in the early 1970s and subsequently moved into home recording with synthesizers and electronics, recording some of the material for Tempus Fugit, his first electronic release, as early as 1974. Over the course of his time as IEMA music director, Moore curated six tapes compiling IEMA members’ work. He subsequently digitized the contents of the tapes and worked with Hal McGee to release the files on McGee’s Bandcamp site. The first tape, originally distributed in 1981, is now available online.

IEMA Collective Group Tape #1 contains ten tracks by five members. Zon Vern Pyles, who currently is a synthesist and sound designer creating soundtracks for film, television and radio, is represented by two tracks built around rapidly pulsing ostinati with overlaid melodies. Pyles’ compositions, with their sophisticated harmonic movement and melodic development, recall the symphonic rock that was being made by progressive rock groups of the time. Jonn Serrie, like Pyles now a working composer and soundtrack artist, contributes two tracks of atmospheric, drifting space music. Moore, whose current work encompasses electroacoustic experiments with gongs as well as more conventional music, provided two tracks of open-textured, largely timbral exploration. Leon Lowman, who is now a visual artist working with collage and abstraction, has three tracks featuring basic rock chord progressions laid out in propulsive triplets. An excerpt from a longer piece by Finch is perhaps the most experimental of the ten, largely eschewing conventional harmony and melody in favor of musique concrète, collage and sound-based exploration.

The Bandcamp release of the first IEMA group tape comes shortly after Vinyl on Demand’s release of multi-LP collector’s editions of music from the cassette underground—a perhaps ironic case of one purportedly obsolete sound reproduction technology preserving the work of another. In addition to a twelve-LP set simply titled American Cassette Culture Recordings 1971-1983, VOD has issued box sets devoted to the early work of individual cassette culture artists such as Moore, Lowman, Slepian, Galen Herod, Steve Roach and K. Leimer.

From the perspective of 2016, the cassette underground inevitably will appear to have operated within the narrow constraints of a technologically limited means of sound creation and reproduction, and under the handicap of inefficient systems of physical distribution and communication. And yet these same conditions fostered a remarkable democratization of creativity and a body of music of continuing, as well as historical, interest.

Thanks to Ken Moore for sharing his reminiscences about the IEMA.